As an instrument of oppression and control, modern police departments are deeply rooted in some of the most racist and repressive colonial institutions of the United States. Since the establishment of the first policing systems like the Night Watch, the Barbadian Slave Code, the urban Slave Patrols, to the “professional” police forces and other law enforcement agencies, every one of these organizations has had the task of surveilling and controlling the population while imposing and upholding colonial law mainly through the use of force and coercion.

US police force was modeled after the British Metropolitan Police structure ; however, the modus operandi –especially when policing poor working class, migrant, brown and black neighborhoods- in the present, resembles the procedures of the 18th century Southern slave patrols, which developed from colonial slave codes in slave-holding European settlements in the early 1600s.

COLONIAL LAW ENFORCEMENT

Essentially every colony in the western hemisphere, be it French, Spanish, Portuguese or English, had difficulties when it came to controlling its slave population and designed similar systems to manage the problem.

As early as the 1530s, runaway Indigenous and African slaves already presented a problem for Spanish invaders in the regions now known as México, Cuba and Perú. Some of the first recognized precursors of slave patrols deployed in the 1530s were the volunteer militia Santa Hermandad or the Holly Brotherhood, which chased fugitives in Cuba. TheHermandad had been established in Spain in the 15th century to repress crime in rural areas and then transferred to the Spanish colonies. The Hermandad was later replaced by expert slave hunters known as rancheadores, who regularly employed brutal tactics. These slave catchers used ferocious dogs to capture escapees. In Perú, enslaved and free blacks “owned by the municipality of private individuals” aided the Spaniard Cuadrilleros in Lima in the apprehension of runaways starting around the 1540s.

Administrators of the Spanish and Portuguese empires passed laws to handle slave-related situations, including the capture and punishment of renegades. Eventually, every Caribbean island and mainland settlements created their own rules and regulations and used a combination of former slaves, paid slave catchers, and the militia as apprehenders, all of them forerunners of patrols.

By the 1640s, Barbados, an English colony, had put in place a formal military structure which included white males, obviously but also indentured servants and even free blacks whose primary functions were patrolling slaves and protecting the island of foreign attacks.

“Though there be no enemy abroad, the keeping of slaves in subjection must still be provided for.” - Barbados Governor Willoughby

Years later other English island and mainland colonies adopted the Barbadian slave code as a model, including Jamaica in 1664, South Carolina approximately in 1670, and Antigua in 1702.

SLAVE PATROLS IN THE SOUTHERN COLONIES

The slave patrols emerged from a combination of the Night Watch, used in Northern colonies, and the Barbadian Slave Code initially employed by Barbadians settlers in South Carolina in the early 1700s.

As the Southern colonies developed an agricultural economic system, the slave trade became indispensable to keep the economy running. African slaves soon outnumbered whites in some colonies and the fear of insurrections and riots led to the establishment of organized groups of vigilantes to keep them under control.

In The Suppression of the African Slave-Trade to the United States of America 1638 – 1870, W.E.B Du Bois quotes South Carolinian authorities: “The great number of negroes which of late have been imported into this Colony may endanger the safety thereof.” And “…the white persons do not proportionately multiply, by reason whereof, the safety of the said Province is greatly endangered.”

All white men aged six to sixty, were required to enlist and conduct armed patrols every night which consisted of: Searching slave residences, breaking up slave gatherings, and protecting communities by patrolling the roads. Historian Sally E. Hadden, notes:

“In the countryside, such patrols were to ‘visit every Plantation within their respective Districts once in every Month’ and whenever they thought it necessary, ‘to search and examine all Negro-Houses for offensive weapons and Ammunition.’ They were also authorized to enter any ‘disorderly tipling-House, or other Houses suspected of harboring, trafficking or dealing with Negroes’ and could inflict corporal punishment on any slave found to have left his owner's property without permission. ‘slave patrols’ had full power and authority to enter any plantation and break open Negro houses or other places when slaves were suspected of keeping arms; to punish runaways or slaves found outside their plantations without a pass; to whip any slave who should affront or abuse them in the execution of their duties; and to apprehend and take any slave suspected of stealing or other criminal offense, and bring him to the nearest magistrate.”

Free blacks and “suspicious” whites who associated with slaves were also supervised. Slaves lived in a state of trauma and paranoia due to the terror that these patrols instilled in them. Various former slaves from different colonies provide an account of their daily lives.

“[A runaway] was with another, who was thought well of by his master. The second of whom… killed several dogs and gave Messrs, Black and Motley (patrollers) a hard fight. After the Negro had been captured they killed him, cut him up and gave his remains to the dogs.” - Jacob Stroyer (Neal, 2009)

“Running away… the night being dark… among the slaveholders and the slave hunters… was like a person entering the wilderness among wolves and vipers, blindfolded.” - Henry Bibb (Neal, 2009)

Rather than punishing, the primary purpose of this racially focused law enforcement was to, “prevent mischief before it happened”. Racial profiling became the fundamental principle of policing and the definition of law enforcement came to be white –and whitewashed- patrolmen watching, detaining, arresting and beating up people of color.

In an effort to establish a consistent surveillance and identification system, the slave pass, one of the earliest forms of IDs, was created to prevent indentured Irish servants from fleeing their master’s property, to identify Native Americans entering white colonies to trade, and to limit mobility of black slaves, of course. Still, thousands of slaves and indentured servants managed to escape into Spanish Florida, the Appalachian Mountains and the big coastal towns where, “a fugitive could mix into the large populations of free blacks and skilled slaves... (surviving)… much like the undocumented immigrants of today, hated and hunted by white society but useful to small craftsmen and other employers who hired their labor at submarket wages.” (Parenti, 2003)

After the Civil War white slave owners realized that race as obvious criteria for conviction or punishment was no longer “legal” – in theory at least. Slave patrols were officially terminated at the end of the Civil War, but their functions were taken over by other Southern racist organizations. Their law-enforcement aspects; detaining “suspicious” persons, limiting movement, etcetera, became the duties of Southern police agencies, while their more violent and lawless aspects were taken up by militia groups like the Ku Klux Klan.

1800S; THE BIRTH OF THE MODERN POLICE DEPARTMENTS

Establishing the exact date to mark the beginning of modern policing in the United States is difficult, since the evolution of older systems like the Constables, Night Watches, and slave patrols into the “new police” was slow. However, we can take the mid-1800s as the years in which the present system of law enforcement dependent on a permanent agency with full-time paid officers was first conceived.

Among the first cities in the country to create such agencies were Boston in 1838, New York in 1845, Chicago in 1851 and St. Louis in 1855; and again, the motive behind the creation of these “peacekeeping” forces was the need to control the “unruly” classes as the emerging industrial economy and new Victorian standards of “morals” demanded it.

Starting in the early 1830s, a chain of riots triggered by race, religious and labor disputes, swept across various cities in the northern region of the country and authorities responded by assigning their Night Watch patrols the riot control function, but they soon learned that a volunteer watch system was ineffective. Day watches also proved to be useless. Full-time, police officers were needed.

“The process of capitalist industrialization led to increasing economic inequality and exploitation and class stratification. Rioting became an essential political strategy of an underclass (a surplus population) and a working-class suffering this increasing economic deprivation. The modern system of policing evolved to control this riotous situation.” (Eitzen, Timmer 1985)

“New York City had so many racial disorders in 1834 that it was long remembered as the "year of the riots”. Boston suffered three major riots in the years 1834 to 1837, all of which focused on the issues of anti-abolitionism or anti- Catholicism. Philadelphia, the ‘City of Brotherly Love,’ experienced severe anti-Negro riots in 1838 and 1842; overall, the city had eleven major riots between 1834 and 1849. Baltimore experienced a total of nine riots, largely race-related, between 1834 and the creation of its new police in 1857. In a desperate attempt to cope with the social disorder brought about by this conflict, America's major cities resorted to the creation of police departments.“ (Williams, Murphy 1990)

The concept of a professional police force was copied from London’s Metropolitan Police Department which had been established in 1829. These “peace” agents were called Peelers or Bobbies after Sir Robert Peel, founder of the institution. The American version of these agents was known as coppers because they wore copper stars as badges on their uniforms. They were available 24/7, carried guns and were “trained to think of themselves as better than the working class they were recruited from.”

In order for the police force to be effective, Peel believed it should work under his Principles of Law Enforcement which explicitly stated an ideology summarized in the following nine points:

- The police exist to prevent crime and disorder.

- Police must maintain public respect and approval in order to perform their duties.

- Willing cooperation of the public to voluntarily observe laws must be secured.

- Police use of force depends on the degree of cooperation of the public.

- The police must be friendly to all members of society while enforcing the law in a non-biased manner.

- Use of physical force should be used to the extent necessary to secure the compliance of the law.

- Police are the public and public are the police.

- Police should protect and uphold the law not the state.

- Efficiency is measured by the absence of crime and disorder.

These principles seemed flawless in theory but in practice they would prove difficult to implement in the United States. Soon after their establishment, police agencies were taken over and driven by political forces. Politicians would hire, and appoint police employees and high ranking officers as they pleased resulting in corruption, nepotism and favoritism being common in police departments around the country. Years later, reformers would try to purge these and other dishonest manners from the police of the “political era”.

Being a British model, the new police had a strong Victorian influence which placed yet another burden on the back of those being monitored; namely, the working-class. Victorian morality dictated strict legal definitions of public order and behavior, especially for womyn who already had to cope with gender and class constraints.

“(W)omen were held to higher standards and subject to harsher treatment when they stepped outside the bounds of their role. Women were arrested less frequently than men, but were more likely to be jailed and served longer sentences than men convicted of the same crimes.”

"Fond paternalistic indulgence of women who conformed to domestic ideals was intimately connected with extreme condemnation of those who were outside the bonds of patronage and dependence on which the relations of men and women were based.” (Williams, 2007)

Despotic hierarchical power relations not only between womyn and men, but also between, lower classes and the state itself were further exacerbated by the introduction of this new policing force as “immoral” conduct, other working-class leisure-time activities and poverty were officially criminalized and more arrests were made based on discretion and initiative of government officers rather than in response to specific complaints.

By the early 1900s, the police was well established as the most notorious state authority figure. Government became omnipresent by means of a more sophisticated surveillance system -over extensive geographical areas- that included, motorized patrols, wanted posters, informants, lineups, detectives, and radios.

“THE REFORM ERA”

The 1920s-1930s reformers’ attempt to remove political influence from police – and vice versa- gave way to a more “professional” police, but in principle it remained the same.

A soft approach for restructuring the institution was taken at first. This proposal estimated that police officers could turn into some sort of “social scientist” collaborating with social workers and teachers to understand what the roots of crime and social instability were. In the end, a more enforcement-like strategy, with a “scientific and technologically advanced methodology of social control” which included a “machine-gun” school of criminology and a stricter legalistic framework was developed. In 1934, FBI Director, J. Edgar Hoover, would attach the concept of war to policing when he declared the first “war against crime”.

“Hoover liked to compare law enforcement officers to the soldiers and sailors who protect the state in times of war. Law enforcement was an instrument of law against disorder, a strategic weapon of war to be used against an internal enemy that was to be eradicated as an enemy of state” (Barry, 2011)

This reform coincided with one of the hardest times for the working class in the country. For disenfranchised workers, strikes and riots –especially during and economic depression, became the way to express discontent not just over low wages and working conditions, but over a lack of economic and political power as well. This obviously meant a threat for corporate elitists and their governmental allies, who didn’t hesitate in sending their armies of police officers to break and repress sit-ins and rallies. Soon, the police were on the streets carrying out some of the bloodiest massacres of “enemies of the state” during the strike waves of the 1930s like: The Memorial Day Massacre in Chicago (1937), the Battle of the Running Bulls in Flint (1937), the Battle of the Overpass in Dearborn (1937), and Bloody Friday in Minneapolis (1934) to mention a few.

In the next decades, the police, FBI, DEA and other law enforcement agencies, would repress, infiltrate and destroy organizations like the Black Panthers Party, American Indian Movement, and the Weather Underground, which the state and the owning classes perceived as threats to the capitalist white supremacy.

LAW ENFORCEMENT IN THE PRESENT

Based on the experience attained dealing with Indigenous Nations, African slaves and other threats, the state has constantly updated and perfected its strategies. One practice remains untouched in today’s policing and law enforcing methods, though; the tradition of upholding the kind of laws that made possible slavery, racism, segregation and discrimination in the country.

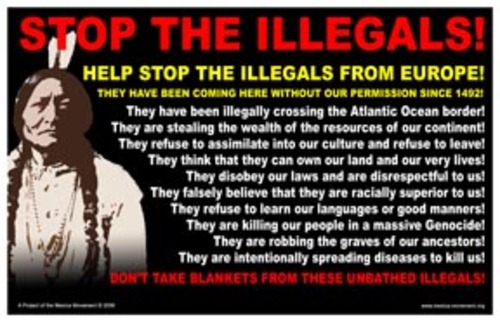

In the 21st century, police attitude towards poor communities of color still resembles that of its precursors 300 years ago. If we substitute the words "slave patrols" for "police departments" and to the list of "Native Americans" and"slaves" we add "undocumented migrants", "Muslims", "political activists", etcetera, we’ll see that the narrative history of our peoples in the United States hasn’t changed much.

Analyzing police slogans like: “To Protect and to Serve” and “Committed to Excellence”, in a historical context, it becomes obvious that they’re not directed at the policed neighborhoods but at those in positions of power, since most of the time interactions and “dialogue” with working class, migrant, and communities of color in general, are reduced to what has legitimated the institution in the first place; abusive behavior and the monopoly of “legalized” violence.

In conclusion, a phrase by Williams Hubert and Patrick V. Murphy is enough to describe the history of law enforcement in the United States:

“Policing by the law for those unprotected by it”

NOTES

- Hadden, Sally (2001) Slave patrols: law and violence in Virginia and the Carolinas. Harvard University Press.

- La Rosa Corzo, Gabino (2003) Runaway slave settlements in Cuba: resistance and repression. University of North Carolina Press Books.

- W. Neal, Anthony (2009) Unburdened by conscience: a black people's collective account of America's ante bellum south and the aftermath. Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America.

- W.E.B. Du Bois. The Suppression of the African Slave-Trade to the United States of America 1638 – 1870 A Penn State Electronic Classics Series Publication. 25 Dec. 2011.

- C. Rucker, Walter, and James N. Upton (2007) Encyclopedia of American race riots. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc.

- Hubert Williams and Patrick V. Murphy, The Evolving Strategy of Police: A Minority View. Department of Justice and Harvard University, December 1989.

- Williams, Kristian (2004) Our Enemies in Blue: Police and Power in America. Soft Skull Press.

- Parenti, Christian, (2003) The soft cage: surveillance in America from slavery to the war on terror. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- G. Forte, Matthew, (2000) American police equipment: a guide to early restraints, clubs and lanterns. Upper Montclair, NJ: Turn of the Century Publishers.

- R. Greene, Jack (2007) The encyclopedia of police science, Volume 1. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis Group, LLC.

- Barry J. Ryan (2011) Statebuilding and Police Reform. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Eitzen D. Stanley and Doug A. Timmer (1985) Criminology: crime and criminal justice. University of Michigan: Wiley.